The Whale Pages: Reproductive Conflict in Killer Whales

- CWR Staff

- Aug 1, 2017

- 2 min read

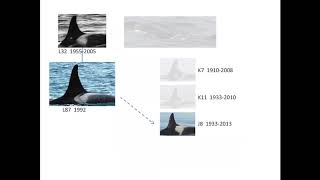

J17 with her youngest daughter J53

Every year for the past 9 years the Center has written a weekly segment in the local paper, the San Jun Journal, in the month of August. These informational articles are called "The Whale Pages". Below is the first installment of the four part series.

Resident killer whales are one of only three species known to experience menopause. Much like humans, female killer whales usually have their last offspring in their late 30s, but live much longer- often into their 80s and beyond.

Why females of any species should stop reproducing before the end of life is an evolutionary mystery. Previous research into this intriguing topic has been hindered by the lack of data from wild animal populations.

The Center for Whale Research has been collecting demographic and social data on the southern resident killer whales since 1976. This dataset represents a unique opportunity to investigate why females might choose to stop reproducing before the end of life. Working with the Center for Whale Research, scientists from the Universities of Exeter and York in the UK have been investigating this problem using the Center’s unique dataset. Mathematical models have suggested that the key to understanding why menopause has evolved might lie in the resident killer whales’ social system. Unlike most mammals, both male and female killer whales stay with their mother for their entire life. A consequence of offspring staying with their mother is that it increases the chances of competition between relatives. Using the Center’s southern resident dataset, along with data on the northern residents, the researchers found that if mothers and daughters reproduce at the same time the mother’s (the older generation’s) calf has a 1.7 times higher risk of dying than the daughters offspring. This competition between relatives provides a reason why females might stop reproducing around midlife - when their daughters begin to reproduce. After stopping reproducing, females continue to be very important to their group.

Using the Center’s data the researchers have shown that older, post-reproductive, females act as stores of knowledge- leading the group especially when salmon are scarce. The importance of these older females to their group is highlighted by the finding that the risk of an adult male dying is 8-fold higher in the years following their mother’s death. This research into the southern resident population has shown that it is a combination of the help that older females can provide the group, and the competition caused by reproducing at the same time as their daughters that drives the evolution of menopause. This unique population, and the data that has been collected about them, has begun to unlock the mystery of why females of some species stop reproducing midway through life.

.

Comments